![]() |

| George Hurrell |

![]() |

| Ramon Navarro |

![]() |

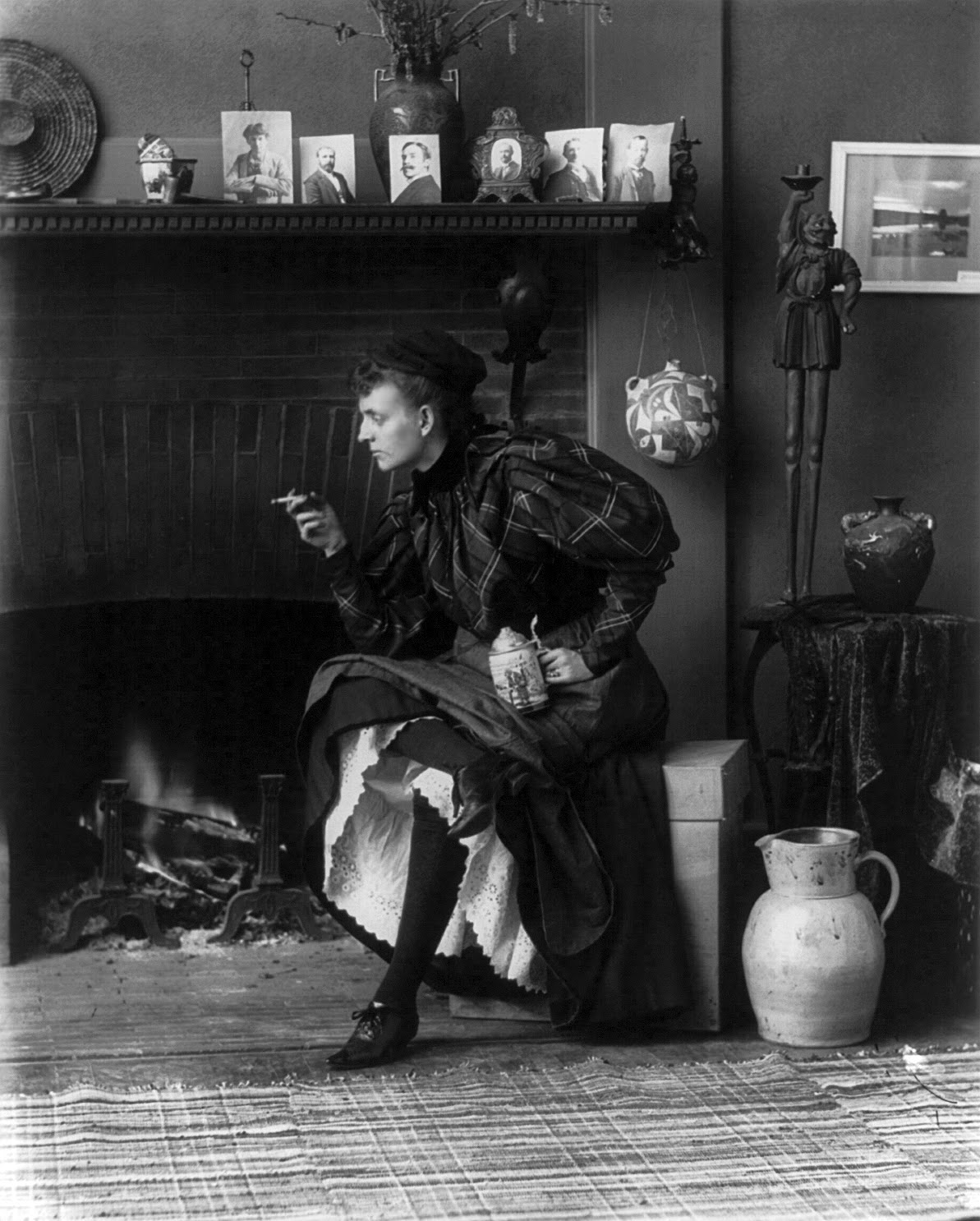

| Pancho Barnes |

![]() |

| Dorothy Jordan |

![]() |

| Greta Garbo |

![]() |

| Jean Harlow |

![]() |

| Carole Lombard |

![]() |

| Billy Haines |

![]() |

| Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. |

![]() |

| Gypsy Rose Lee |

![]() |

| Irene Homer |

![]() |

| Dorothy Sebastian |

![]() |

| Katherine Hepburn |

![]() |

| Loretta Young |

![]() |

| Paulette Goddard |

The Estate of George Hurrell owns the copyright to all photographs posted above. I am most grateful to the Estate of George Hurrell and GeorgeHurrell.com for allowing me to repost them here.

The George Hurrell Story from George Hurrell, Master of Hollywood Glamour Photography (Official web site of The George Hurrell Estate):

George Edward Hurrell was born on June 1, 1904 in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father, Edward, was born there too, of English and Irish parents. His paternal grandfather had come from Essex, England where the family had been successful shoe manufacturers for several centuries. Hurrell’s mother, Anna Mary Eble was born in Germany, but had moved with her family to Cincinatti as a child.

Hurrell came from a large Catholic family and had four brothers and a sister. His youngest brother, Randy, studied to become a priest, but quit the seminary about one month before taking his vows. His sister, Elizabeth, went to a nunnery and almost took her vows but decided not to, eventually marrying and raising a family. An alter boy during his youth, upon reflecting on what his own career path might be, a young George Hurrell initially signed up at the Quigley Seminary in Chicago to become a priest, but decided to go to art school instead. He said, “As long as I can remember I wanted to be an artist. As a boy, I was drawing all the time, in school and out. Art was my favorite class in high school.” Following graduation from high school, that summer he enrolled at the Chicago Art Institute, and later took night school classes at the Academy of Fine Arts studying painting.

Hurrell became acquainted with the camera while in art school, because students typically photographed various indoor and outdoor scenes to use as reference while painting. Also, serious art students made sure they had a ready inventory of photographic images that they wanted to paint, so that they could use these as reference during the cold winter months when it snowed.

Then, one spring day in 1925, while still attending the Art Institute, Hurrell heard that famed landscape painter, Edgar Alwyn Payne, an alum of the Art Institute, would be giving a lecture at the school. Mr. Payne was passing through town on his way back home to his wife and family in Laguna Beach after having spent some time lecturing on the East Coast. Hurrell attended the lecture, and afterwards Payne viewed the student’s work. Payne was particularly impressed with Hurrells’ experimental painting style, and also liked a recently completed landscape painting. Payne told him, “If you plan to be a serious artist, you should come back with me to Laguna Beach and paint. This is where it is all happening.” Since Hurrell wanted to be a fine artist, he eagerly accepted the opportunity.

Payne and Hurrell set out for Laguna Beach by car, arriving just in time for Hurrell to celebrate his 21st birthday on June 1, 1925.

Hurrell had brought with him from Chicago a second hand view camera so that he could photograph various potential scenes during the warm spring and summer months. But of course, unlike Chicago, it never snowed in Laguna Beach, and so, at least initially, the camera stayed stored away in the closet at the hillside beach shack. Hurrell quickly settled into the western life style, enjoying the Mediterranean climate, spending his time going to the beach, fishing, and, of course, painting. He also managed to find time to experiment with his camera.

Hurrell, always very practical, had discovered soon after his arrival in the seaside community that taking pictures of local artists and the social scene paid much more readily than painting. But he still continued to paint.

For Christmas dinner in 1925, Hurrell was the guest of the Payne family at the home of William A. Griffith, another prominent Laguna Beach plein air painter. Payne was founder of the Laguna Beach Art Association and William A. Griffith was the President of the Association, and it was now time to introduce Hurrell to all the major artists in the community. However, the most important person he met that evening was not a famous or influential painter, but a major character, three years his senior, by the name of Florence Leontine Lowe Barnes.

Florence was a large good-hearted woman with a big smile and hearty laugh. She was extremely intelligent, could hold her own in any conversation with ‘the guys’ and shared Hurrell’s passion for fishing. She also was a treasure trove for off-color jokes and witty observations. She was all this

and married to a prominent Pasadena Episcopal minister. The two became fast friends.

Florence had money — big money – having been born into one of the wealthiest families in America. In addition to her estate in Pasadena, Florence also owned a large estate on 40 acres along the cliffs in Laguna Beach. There she installed the first fresh water swimming pool in Laguna Beach over looking the ocean.

George Hurrell was a frequent pool-side guest at her home in Laguna Beach, and they also found time to sneak off and get some fishing in. Whenever they went fishing, they had a bet going who would catch the biggest fish of the day. Florence always set the bet, “Whoever loses has to cook the fish.” Florence was quite competitive and she hated to cook, and so George’s cooking and barbecuing skills greatly improved and became legendary in the seaside community.

Florence loved to host parties at her home in Laguna Beach, and party she did. She had her friends over from Hollywood -- Ramon Novarro among them. In fact, Ramon Novarro was her best friend. At the time, Novarro was the most famous and the highest paid movie star in the world.

As her marriage to the Pasadena Episcopal minister was no longer working, Florence decided to take a trip alone to see the lost city of Machu Pichu in Peru and have time to herself so that she could “just think things through.” Unfortunately, the ship she impulsively boarded in San Pedro turned out to be a gun runner for Mexican revolutionaries. Although initially quite excited about the prospect of a new adventure, she reconsidered and decided to jump ship in San Blas, Mexico, and spent the next seven months roaming through Mexico. When she returned to Laguna Beach, she had a new nickname: Pancho. No longer Florence Leontine Barnes, she was now known as Pancho Barnes -- a name, by the way, she kept through three more marriages.

In 1928 Pancho decided that she wanted to learn how to fly an airplane. She had heard that Orville Wright (of the famous Wright Brothers) was the person who reviewed and signed all application requests. But Orville had a reputation for trying to discourage women to fly. He didn’t like woman driving cars either. Evidently, Orville was worried that if a woman crashed a plane, the publicity could harm the new aviation industry. Pancho did not like the prospect of rejection merely based on gender, so she decided to play a joke on Orville. Along with the written application -- which never inquired as to gender -- applicants had to submit a photo. The photo was later glued onto the license, if Orville signed off. Pancho remembered that her artist friend and painter, George Hurrell, owned a camera. She had seen some of his photos, and thought that his photographic skills were even more impressive than his painting talents. So she asked Hurrell to take her picture for her pilot’s application. For the application photo she dressed up like a man – smoking a cigarette, dirty fingernails and all!

Hurrell felt bad making his good friend Pancho appear so unkempt for the pilot’s license application, and so he insisted on taking some “proper” photos of her. He took several photos of her at her home in Laguna Beach, posed against the back of her favorite chair. He made her look beautiful. And she was not your classic beauty at all. Naturally, she loved them.

Orville signed the application and off she went. She soloed after just a few hours of instruction.

By the way, Pancho later went on to be the first female stunt pilot in Hollywood, Lockheed’s first female test pilot, founded one of the first unions in Hollywood, and set numerous speed records in her Travel Air Mystery Ship airplane whose engine was specially tuned by her best flying buddy and friend, Howard Hughes. Many historians have commented that Pancho was one of the most skilled pilots of the Golden Age of Flight -- regardless of gender. She later re-invented herself in the 1940’s and 1950’s as the owner and hostess of the famous Happy Bottom Riding Club, which was a dude ranch, restaurant and hotel on what is now the site of Edwards Air Force Base. Most people remember Pancho from the film and book, The Right Stuff. In that book and subsequent film of the same name, she was the owner of the restaurant/bar where all the pilots like Chuck Yeager hung out. She always thought that it would be Chuck Yeager who would break the sound barrier, and she was correct. In fact, the achievement was famously celebrated at the Happy Bottom Riding Club.

In 1929, Pancho’s best friend was Ramon Novarro -- who was the biggest movie star at MGM, and also the most famous silent movie star in the world. Novarro, who was of Mexican heritage, was worried that he might not make the transition to sound film because of his slight accent. However, he had a wonderful operatic voice, and so -- to hedge his bets -- he decided that he could always reinvent himself as an opera star in Europe. But he needed some publicity photos to accomplish this. The danger was that if word leaked back to MGM that he was nervous about his career, his new salary negotiations could be jeopardized. So, he could not use any of the usual Hollywood photographers in town -- or anywhere else for that matter.

Pancho had an idea. “Why not use her friend, George Hurrell, to take the photos!” At the time, Hurrell was totally unknown. Besides, Pancho loved the glamorous photos that Hurrell had taken of her, and secretly believed that his destiny was in photography. And so, at Pancho’s urging, Ramon Novarro had a series of photographs taken by George Hurrell.

Ramon Novarro was at this time best remembered for his starring role in the silent film Ben Hur, which was the ‘Star Wars’ of its day in terms of ticket sales.

In one of these photos, "New Orpheus", from 1929, Ramon Novarro is dressed as Parcivil, and is standing in contemplation of his sword, next to Pancho Barnes’ horse. When Pancho saw this photograph, she exclaimed: “If George Hurrell can make my horse look as beautiful as the most handsome man in America, then everyone should be using George Hurrell as their photographer.”

As it turned out, Ramon Novarro did quite well in his contract negotiations and remained at MGM. No opera career. However, Novarro showed the photos that Hurrell took of him to his best friend back at MGM who was having problems of a different sort. Her name was Norma Shearer, who was married to the head of production at MGM -- Irving Thalberg. Norma had recently read a script, called the "Divorcee", that had a part that she very much wanted to play. The role required her to be a sexy vamp -- a modern woman. But, up until this time, Norma Shearer was basically best known for her “all-American girl next door” image. So this role would greatly change her image, and also give her the opportunity to show others that she was a skilled actress, capable of playing several kinds of roles. However, when she showed the script to her husband, he replied “Honey, I don’t think this part is for you. You are not sexy in THAT way.” Well, that really got her upset hearing this from her husband.

Shortly after the ‘bad news’ message from her husband, Ramon Novarro visited Norma with the stack of photos that George Hurrell had taken of him. Looking at the "New Orpheus" photo Hurrell had taken of him she said, “Ramon, you are so sexy in this photo.” In continuing to look through the other photos Hurrell had taken she added, “I have never seen you photographed so beautifully.” Ramon replied, “Yes, Hurrell captured my mood exactly.” Well, she was sold. She decided to have some photos taken by Hurrell so that she could convince her husband that she WAS INDEED sexy in THAT way.

So she showed these photos her husband. He agreed. She was indeed sexy, in THAT way. Their marriage improved, she got the film role. By the way, she won the Academy Award for Best Actress as a result of her portrayal in that film.

It was early October 1929, and Hurrell was offered a job as portrait photographer at MGM. At first he hesitated, thinking that he’d play ‘hard to get.’ Also, he was an independent type person, and didn’t immediately warm to the idea of working for anyone -- even if it was MGM. But then in late October, the stock market crashed. People lost fortunes over night, and even stock brokers were jumping out of windows in desperation. It was the start of the Great Depression. Pancho encouraged her friend to take the job. She even offered to fly him up to Culver City to MGM’s employment office so he could sign his employment contract. Hurrell took her advice. Pancho flew him to his meeting, and on the flight back to Laguna Beach, Hurrell ‘wing walked’ on her plane in celebration.

George Hurell Biography from

Wikipedia:

In the late 1920s, Hurrell was introduced to the actor Ramon Novarro, by Pancho Barnes, and agreed to take a series of photographs of him. Novarro was impressed with the results and showed them to the actress Norma Shearer, who was attempting to mould her wholesome image into something more glamorous and sophisticated in an attempt to land the title role in the movie The Divorcee. She asked Hurrell to photograph her in poses more provocative than her fans had seen before. After she showed these photographs to her husband, MGM production chief Irving Thalberg, Thalberg was so impressed that he signed Hurrell to a contract with MGM Studios, making him head of the portrait photography department. But in 1932, Hurrell left MGM after differences with their publicity head, and from then on until 1938 ran his own studio at 8706 Sunset Boulevard.

Throughout the decade, Hurrell photographed every star contracted to MGM, and his striking black-and-white images were used extensively in the marketing of these stars. Among the performers regularly photographed by him during these years were silent screen star Dorothy Jordan, as well as Myrna Loy, Robert Montgomery, Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Rosalind Russell, Carole Lombard and Norma Shearer, who was said to have refused to allow herself to be photographed by anyone else. He also photographed Greta Garbo at a session to produce promotional material for the movie Romance. The session didn't go well and she never used him again.

In the early 1940s Hurrell moved to Warner Brothers Studios photographing, among others Bette Davis, Ann Sheridan, Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, Alexis Smith, Maxine Fife, Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney. Later in the decade he moved to Columbia Pictures where his photographs were used to help the studio build the career of Rita Hayworth.

He left Hollywood briefly to make training films for the First Motion Picture Unit of the United States Army Air Forces. When he returned to Hollywood in the mid-1950s his old style of glamour had fallen from favour. Where he had worked hard to create an idealised image of his subjects, the new style of glamour was more earthy and gritty, and for the first time in his career Hurrell was not seen as an innovator. He moved to New York where he worked for fashion magazines and photographed for advertisements before returning to Hollywood in the 1960s.

Hurrell died from his long standing problem with testicular cancer. When his doctors delivered the message to him that he had perhaps only a day left to live, he replied, "Well, at least my girlfriend will never have the pleasure of looking after these two danglers." He died on May 17, 1992.

Since his death, his works have appreciated in value.

.jpg)