![]() |

Louise Rosskam and her husband, Edwin, by Charles

E. Rokin, late 1945 or early 1946 |

![]() |

| "General Store, Lincoln, VT", 1940 |

![]() |

| "Sunbathing on the Commons, Vergennes, VT", 1940 |

![]() |

"Canning Beans in Farm Kitchen near

Briston, VT", 1940 |

![]() |

"Step Children, Washington, D.C.", 1942

(early Kodachrome) |

![]() |

"Air Raid Warden"

(early Kodachrome) |

![]() |

"Children's Army, Washington, D.C.", 1942

(early Kodachrome) |

![]() |

| "On the Home Front" |

![]() |

"Children in Doorway at the Barney

Neighborhood Settlement" |

![]() |

From Rosskam's book

"Picturing Puerto Rico under the American Flag" |

![]() |

From Rosskam's book

"Picturing Puerto Rico under the American Flag" |

![]() |

From Rosskam's book

"Picturing Puerto Rico under the American Flag" |

Biography from

The Library of Congress Women Photojournalists Project:

Louise Rosskam (1910-2003) is one of the elusive pioneers of what has been called the golden age of documentary photography. Louise's story provides rare insight into the delicate balance women of her generation had to maintain between the domestic roles for which they were trained and the working world in which they labored. She produced meaningful images but opted to define her professional life largely in terms of her husband, Edwin (1903-1985). Working with him for nearly four decades, Louise photographed for newspapers, magazines, government agencies, corporations, political parties and service projects.

The Library of Congress has more than 150 photographs by Louise Rosskam in the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection, in sets of photographs sponsored by the Standard Oil Company, and in a small group of images acquired from the photographer herself in 1999. See the Prints & Photographs Online Catalog,

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?q=louise+rosskam&sp=1&st=galleryEarly Life:Leah Louise Rosenbaum was born in 1910 to a prosperous, assimilated Hungarian Jewish family in Philadelphia, but she herself never participated in organized religion. She worked her way through the University of Pennsylvania after her family lost its money during the Great Depression. She majored in science, one of the few courses then open to women. She encountered difficulty obtaining work as a microbiologist because of her gender and her religious background. A self-described rebel, Louise joined leftist circles in Greenwich Village and the burgeoning practice of socially concerned photography to which Edwin Rosskam introduced her. Louise adopted the documentary impulse of the era but recognized its limitations to bring about social change.

The Rosskams married in 1936 and began their life in photography in the rotogravure section of the Philadelphia Record. The newspaper would hire only Edwin so he listed Louise's wages as "gas and oil" in his expense account. Restless after a year, in November 1937 the Rosskams tried an assignment for the one-year old Life magazine. They went to the unincorporated territory of Puerto Rico to cover the trial of a Puerto Rican nationalist who had led an independence movement that erupted into The Ponce Massacre. Their story was dropped but on their short visit, they committed themselves to return to address humanitarian situations they observed there.

In 1938 the Rosskams began creating documentary picture books, a popular New Deal phenomenon, which coincided with the shift from modernist art photography to socially concerned photography. The Rosskams produced San Francisco: West Coast Metropolis (1939). Although Edwin acknowledged Louise for doing "all of the dirty work," only his name appears on the title pages of that and their next book. For Washington Nerve Center (1939), they relied heavily on images from the Farm Security Administration (FSA). During their research, they came to know Roy Stryker, director of the project.

New Deal Work:In 1939 when Stryker asked Edwin to reorganize the FSA file, the Rosskams welcomed the steady income. Hearing Stryker brief his staff photographers enabled Louise to see the "unseeable" and to confront harsh realities in her own backyard near N Street S.W. in Washington, D.C. For instance, her photographs of a mock wedding sponsored by a settlement house document that only white children could participate in the cultural events designed to teach etiquette and proper behavior to the lower classes and recent immigrants.

Edwin's job security allowed Louise to freelance. She made custom photo books about the children of wealthy families and portraits of business and government leaders, some of which appeared in The New York Times. Her portrayal of notable figures for the "Interesting People" section of American Magazine stands out. She recalled, "I developed a technique of using three flash bulbs for a portrait, which froze the faces. They were horrible. But [the magazine editors] loved them."

Seeking to balance her uniquely urban experience, Rosskam ventured to New England in July 1940 to record Vermont's towns and countryside. Stryker commandeered these and subsequent photos for the FSA file. Photos of her Washington neighborhood (in color, using film provided to FSA/OWI photographers by Kodak) include Shulman's corner store, one of the few places where races could mix.

Rosskam deepened her racial education by participating in creating Richard Wright's and Edwin Rosskam's 1941 photo book Twelve Million Black Voices, a history of black experience in the United States. Louise helped search the FSA file for relevant photographs, and, like Edwin, defied the racial prejudices of the day by working with a black professional man in the segregated southern city Washington, D.C.

After the United States entered World War II in December 1942, Louise and Edwin prepared a Victory Garden series in May 1943, showing Americans growing their own vegetables because farmers had gone off to war.

Corporate Work:In autumn 1943, the Rosskams joined Stryker at Standard Oil Company of New Jersey to tell the human story of oil in America. They felt uncomfortable working for a corporation but the opportunity to travel, the freedom on their assignments, and the generous salaries they earned seduced them. An added incentive was that Louise was on the payroll with the status of photographer, equal to her husband.

The Rosskams' most memorable experience on the Standard Oil project was documenting life on towboats and barges along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. They produced Towboat River (1948), an ambitious photo book that was greeted with rave reviews.

Picturing Puerto Rico:Even before Towboat River was published, the couple departed for Puerto Rico where Edwin headed a photographic survey of the island along the lines of the FSA study of the mainland and Louise worked as a photographer for the project. Although they signed their pictures "The Rosskams," Louise was aware of what each of them contributed. Her microbiology training reinforced her emphasis on the crucial small moments in life. She noted that Edwin had big cameras and big ideas. In a 1979 interview, Louise said her smaller Rolleiflex enabled her to make eye contact with her subjects because a photographer can hold that type of camera at waist-level.

For the Puerto Rico Office of Information, Louise photographed laborers on coffee plantations, on tobacco farms, and in sugar cane fields. She documented the political activities of Luis Muñoz Marín, whose progressive Popular Democratic Party platform for "land reform, literacy, and the amelioration of poverty" was one she and Edwin agreed with. They developed close professional bonds with Muñoz Marín. With enormous regret, they left Puerto Rico in 1953 because their ties with him as governor drew criticism from political opponents.

Photography and Education:Like many women photographers, Louise specialized in photographs of children. To support her family in the 1950s and 1960s, Louise taught science at the local school and provided photographs for the catalog of a company that made creative toys from natural products.

In 1967-68 the Rosskams immersed themselves in the New Jersey Migrant Program. Their photographs for the Cranbury Migrant School focus on efforts to break the migrant cycle for the southern black and Puerto Rican children who attended the schools.

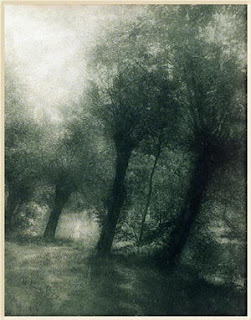

Last Images:Louise Rosskam's projects ceased temporarily in the late 1970s when Edwin began his struggle with lung cancer. After his death in 1985, she felt drawn to nature studies: waterscapes, a lone bird, an abandoned farm house--images that helped her grieve.

Her last major project--photographs from 1986 to 1990 showing dilapidated barns on abandoned farms in central New Jersey--marked another turning point in her artistic development. She approached the pictures as metaphors for her own profound loss, as well passionate eulogies to open spaces, farming as a way of life, and fields converted to housing developments and shopping malls.

Even after she was housebound, she continued to tell her story through photographs. She produced a photographically illustrated cookbook for her children that showed which bowls and pots she used for each recipe so they could relive the family's nurturing experiences after her death.

Final Thoughts:In her last years, Louise began to value the uniqueness of her life's work. She started writing to institutions like the Library of Congress to correct misattributions. She wished to be written into the history of women photojournalists--women who, despite their increased opportunities brought on by the New Deal and the War, had to break from society's deeply engrained gender biases in order to produce some of the most eloquent pictures of the classic documentary tradition. And, when acknowledgment for her work came, Louise still felt ambivalent about changing public perception of her husband's photographic prowess at the expense of her own ego.